I have finally, finally finished Alan Moore's Voice of the Fire. It really shouldn't have taken this long; it surprises me more than anyone. He's my favorite writer, after all, and this is his first, so far only, prose novel, and you would think (as I did) that it would be devoured immediately, in a day or 4.

But that would be doing the book a disservice, and yourself as well. It would be like spending hours to prepare a very complicated dessert and gobbling it all up in a single mouthful, without savoring the experience, without enjoying (or at least trying to enjoy) every ingredient, and the blending of flavors, and its texture, and maybe even its scent.

That said, it still shouldn't have taken this long. I'm talking months. I first mentioned it on this blog on November 12. The short answer is there were long breaks between some of the chapters. Maybe it was the density of the stories; there are ideas contained therein that would infuse hundreds of books in the hands of weaker writers. Partly it was circumstances like work, and distractions like other books, other media; the demands of a social life on life support. The breaks were easy to slip into because each chapter is self-contained; has a different narrator.

But today, finally, I finished it.

And it is marvelous. It is mind-blowing. And too many other adjectives.

There are few delights better than having a work of art not only meet your expectations, but surpass and, AND, do them one better. Or several better, as the case is here. The last chapter of Voice is The Manhattan Project. It is the atom bomb. Similar in impact to my experience with the last chapter of Moore's From Hell, where Jack the Ripper floats through time to witness what he hath wrought upon the world, and history, and consciousness; humanity.

In the last chapter of Voice of the Fire, Moore himself is the narrator. He is the last host of his fiction, which is steeped in research and fact. One of the points he gets at is how the novel, the book, the fiction, which he has been working on for 5 years at that point, has finally, ultimately, consumed him as well: its creator, its author. Another point is how themes emerge, in retrospect: decapitated heads, black dogs, fire (of course), music, etc. Yet another is how things work themselves out, peculiarly: the book's characters sometimes dabble in magic, and in the 5 years that Moore has been working on the book he himself has become a magician (not in the illusionist sense but in the magick, magus sense). So his perspective, that of a magician wrapping up a book of magic that took 5 years to complete, is different from the perspective he began with, 5 years ago, writing about caveboys who are suddenly orphaned. Which surprises Moore, and probably further reinforces his belief in magic.

Maybe I should let him describe it himself, which he does in the last chapter:

"It's about the vital message that the stiff lips of decapitated men still shape; the testament of black and spectral dogs written in piss across our bad dreams. It's about raising the dead to tell us what they know. It is a bridge, a crossing-point, a worn spot in the curtain between our world and the underworld, between the mortar and the myth, fact and fiction, a threadbare gauze no thicker than a page. It's about the powerful glossolalia of witches and their magical revision of the texts we live in. None of this is speakable."

Later:

"Some chapters back, the notion of a shaman with the town tattooed upon his skin, its boundaries and snaking river-coils become a part of him so that he might in turn become the town, a magic of association with the object bound up in the lines that represent it: lines of dye or lines of text, it makes no difference. The impulse is identical, to bind the site in word or symbol. Dog and fire and world's end, men and women lamed or headless, monument and mound. This is our lexicon, a lurid alphabet to frame the incantation; conjure the world lost and populace invisible. Reset the fractured skeleton of legend, desperate necromancy raising up the rotted buildings to parade and speak, filled with the voices of the resurrected dead. Our myths are pale and ill. This is a saucer, full of blood, set down to nourish them."

It's impossible for me to fully convey the impact of this work, if you have not read the book. But there are phrases in the last chapter, like "This is a fiction, not a lie." and "The author types the words 'the author types the words.'" that just open doors and windows in your consciousness, letting starlight and fresh air in. I feel like they should be accompanied with sound effects: the awesome finality of a last jigsaw puzzle piece fitting into place, or the sound of tumblers falling in sequence as a lock is irrevocably undone.

The last chapter is basically Moore walking through the town he loves, pondering the almost-conscious work the book has become, and he writes: "This final chapter is the thing. Committed to a present-day first-person narrative, there seems no other option save a personal appearance, which in turn demands a strictly documentary approach: it wouldn't do to simply make things up." But you realize: every preceding chapter is made up, albeit based on fact, and those very words that purport to convince us that this chapter is faithfully accurate, are part of a chapter, the last of a book, that proudly claims to be a novel. A fiction. The power and potential of fabulation is there, don't you see? Making things up, so to speak, can be as powerful as anything. Transcending the very word "powerful" and whatever we imagine that to be. As if our imaginations could ever be restrained by such a base word. This realization, this superexpanding mushroom cloud of dawning, engulfs everything in its path.

"Although at times unnerving, this was always the intention, this erasing of a line dividing the incontrovertible from the invented. History, unendingly revised and reinterpreted, is seen upon examination as merely a different class of fiction; becomes hazardous if viewed as having any innate truth beyond this. Still, it is a fiction that we must inhabit. Lacking any territory that is not subjective, we can only live upon the map. All that remains in question is whose map we choose, whether we live within the world's insistent texts or else replace them with a stronger language of our own." All of history is a fiction. Keep tugging at that thread, ride that train of thought and you'll arrive at the conclusion that all of it: reality, myth, history, religion, fiction, even lies-- they're all just stories. But I mean this in no reductive way; rather, it's quite the opposite: it may be the most expansive connecting thread there is. Gain some distance from it, and what emerges is: the potential power of effective storytelling is unlimited.

I implore you: if you are a writer, or fancy yourself a writer, or harbor the faintest glimmer of a dream that you will one day tell a story, and shelter that glimmer seriously-- read this book. If you love stories with a passion, read this book. At the very least, you'll get great stories, but I tell you there is so much more to fall in love with: the language, the range of styles, the fossilized terms and phrases, the imagery, the characters...

I started writing this simply because I loved the book, but it has unintentionally grown into something else that is almost unsettling. I finished writing this at 5 AM. The book is THAT GOOD.

--

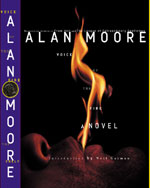

Voice of the Fire is a novel by Alan Moore. It was recently published in a new edition by Top Shelf in the US, in hardcover, with an introduction by Neil Gaiman and 13 color plates by Jose Villarrubia. Book design by Chip Kidd. It was first published in 1996, in paperback and only available in the UK, by Victor Gollancz and Indigo, but these editions are now out of print.

Thanks to Erwin Romulo for lending me his copy. I now have to save up, buy my own, and read it again.

No comments:

Post a Comment